In the book Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages Guy Deutscher reveals today's subject to be highly charged:

In [the] field of language, culture's incursion into the land of concepts so offended, even outraged, plain common sense that for decades the defenders of nature were mobilized to fight to their last drop of ink to uphold her cause. In consequence this enclave has been at the center of a 150-year war between the proponents of nature and of culture, a conflict that is showing no sign of abating."

In a previous post on the language of color, we wrote about a South American tribe with no fixed words for color but instead used real world comparisons like "the color of blood" when describing a red object. We also learned that when humans switch from using these types of comparative color words to using fixed color words the processing of color switches from the right to the left hemisphere of the brain. This week we want to delve deeper into the historic relationship between color language and science. We are going to replay a 150 year old color science debate to see the evolution of color language in action.

|

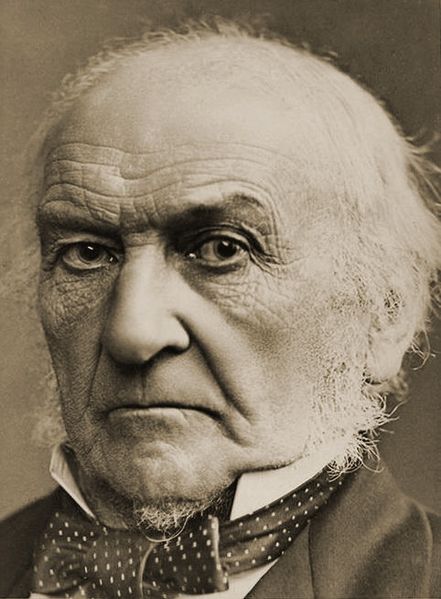

| William Gladstone via Wikipedia |

In it Gladstone introduces the fact the in all of the works attributed to Homer, including the Iliad and the Odyssey, color language differs greatly from modern times. Blue, for example, is never used; instead the frequently used phrase "wine dark sea" appears. Gladstone theorized that this use of language indicated mass colour-blindness in the Greeks. He claimed that "the organ of color and its impressions were but partially developed among the Greeks of the heroic age."

Next to take up the subject was Lazarus Geiger who expanded on Gladstone's ideas by looking at other classic works and hypothesized that man gradually became aware of color over time. He posited the idea that this awareness was connected to the order colors came up in the spectrum, starting with the longest wavelengths. These theories sparked a debate on whether a culture that lacked a name for a color could see that color at all, a argument that developed into the field of Linguistic relativity.

At the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1882, Dr. Montagu Lubbock read a paper On the Development of Colour-sense refuting the claims made by Gladstone, Geiger and several other contributors to the conversation. He wrote that while it is true that ancient writings from around the world did not include certain color words:

"Neither in the Vedas of the Hindus nor in the Zendavesta of the Parsees had [Gladstone] found indications of developed colour perception, any mention of blue colour being entirely absent from both, though the sky ... [was] specially considered. Similarly no mention was made of green colour either in the Rigveda hymns or in the Zendavesta though both often speak of the earth and its vegetation."This doesn't mean that humans developed colour-sense over a few thousand years. He stated that "the arguments in favour of the gradual development of the colour sense in man within historic times were merely philological and that observations among the uncivilised races now living had shown that the extent of the colour perception is not indicated by the variety of terms used to express it." In fact he went on to illustrate the flower insect relationship in early geological time was most likely the first time color vision became an evolutionary advantage. By allowing some insects to see a red flower on an other wise continuously green background, this provided the plant a more dependable method of fertilization.

Its great to see that the language of color was once a hotly debated subject on the cutting edge of science; and that what we think of as over and done with was mulled over and debated by many great minds. Color never fails to fascinate.

- Emily Eifler, Writer, Colour Studio

- Jill Pilaroscia, Principal, Colour Studio

- Jill Pilaroscia, Principal, Colour Studio

No comments:

Post a Comment